Pathogen testing is of major importance to the food industry as there are 31 known bacteria and virus causing pathogens, and more unidentified agents, that cause foodborne illnesses. The elimination of these disease-causing pathogens is a desire for the entire food industry. Food recalls due to pathogen contamination can be disastrous and expensive for all involved. Full traceability and cloud-sharing protocols minimize the risk of erroneous data, which can be a cause of this.

Foodborne illnesses are a major concern for the food industry. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimates that about 1 in 6 people in America or 48 million people are infected with a foodborne pathogen each year. Of those 48 million, 128,000 are hospitalized and 3,000 ultimately die.

Testing is done to reduce, and ultimately eliminate foodborne illnesses. It is a process implemented in every step of food production to ensure sanitation and food safety. The most common foodborne illnesses that pathogen testing is concerned with are salmonella, listeria, and E. coli. Pathogen testing can be done using conventional cell culture standards, or more recent molecular biology techniques based upon PCR.

The incidence of foodborne diseases has increased over the years and resulted in major public health problem globally. Foodborne pathogens can be found in various foods and it is important to detect them to provide safe food supply and to prevent foodborne diseases. These qualitative proficiency tests focus on the detection of the pathogens specified. Proficiency tests aim to improve a laboratory’s detection ability through identification of areas of improvement from which to provide highly credible, repeatable results.

The Importance of Proficiency Testing in Assuring Analytical Laboratories

Proficiency testing has increased in food microbiology laboratories in response to various factors: ISO 17025 accreditation increases, regulatory focus, customer requirements, internal quality requirements and an increase in validation and verification activities.

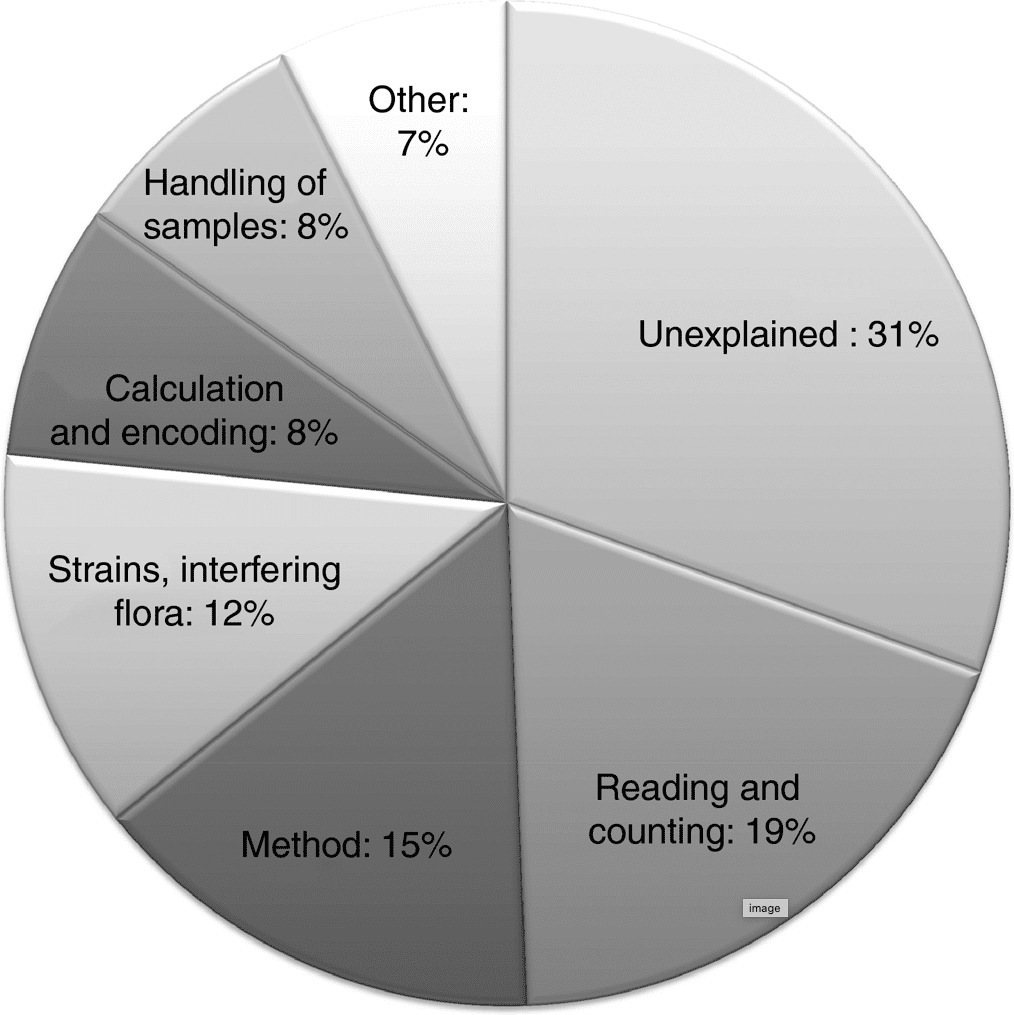

It has been further fuelled by data highlighting causes of inadequate detection of micro-organisms in food. The causes are broken out in the figure below.

Causes of inadequate quantification of micro-organisms (Massih et al, 2015)

With regard to ‘methods’, laboratories are advised to use their routine protocols for the analysis of the PT samples and the variety of the methods used accounted for 15% of the outliers.

When methods are based on different principles (e.g. different protocols, media, temperatures or confirmation techniques), the performances in terms of productivity or precision are not always comparable.

Proficiency Testing use in Food Testing Laboratories

Proficiency testing (PT) is widely used in the food testing industry as a way to verify that an individual laboratory is capable of performing a given analytical method, and to detect possible issues. A PT scheme consists in an inter‐laboratory comparison, based on the analysis of identical samples by different laboratories. The analytical results obtained by the participants are collected by the PT provider and statistically compared to detect false or outlying results. It is then the responsibility of the laboratory to determine the possible causes of the observed errors and to implement corrective actions.

Since 2005, the ISO 17025 standard for the accreditation of laboratories requires regular participation to PT, if available, as a quality control tool (Anonymous, 2005). This process is meant to instigate continuous improvement of the laboratories, as each outlier should be addressed by the laboratory and followed by appropriate corrective actions.

The first PT programmes had been conducted in 1946 in the clinical field, with the aim of demonstrating the reliability of the laboratory analytical results. At the beginning, the participants’ analytical performances were globally poor, revealing high incoherency between laboratories and highlighting the need for external harmonization.

The field of food microbiology has followed the trend of the medical sector, driven by a need for reliable analyses to ensure food safety. Supported by governmental initiatives, numerous food microbiology PT schemes have emerged worldwide in the last 30 years.

Today, the European Proficiency Test Information Service (EPTIS) database lists no less than 120 PT schemes worldwide in the field of food microbiology (www.eptis.bam.de, 2015).

PT schemes represent a unique observation post to study the performances of routine laboratories, to follow the evolution of these performances in time, and to better understand and potentially eliminate the causes of unsatisfactory analytical results. This process is also educational: the interpretation of the PT results can help to highlight the main causes of errors in food microbiology analyses and to suggest areas of improvement to the laboratories.

Full traceability and cloud-sharing protocols minimize the risk of failing a proficiency test

Ensuring full traceability of each step conducted in an analytical workflow can ensure compliance with established regulatory practice as well as troubleshooting any sources of error. It can also ensure that proficiency testing is that much easier to conduct between ‘reference laboratory’ and the laboratory being evaluated. Moreover, the ability to readily share protocols between laboratories, via the cloud, mitigates protocol misinterpretation as a source of error. Learn about how OneLab enables this, here. Full traceability and cloud-sharing protocols minimize the risk of failing a proficiency test

Massih et al., Analytical performances of food microbiology laboratories – critical analysis of 7 years of proficiency testing results, J. Appl. Microbiol., 24 November 2015

Learn more at www.andrewalliance.com